Can’t take a breath this week without stumbling over another particle physics result of note. (It isn’t usually like this, folks — this year has been very odd.) OPERA (the experiment that claims their neutrinos travel faster than light does, which if true would require some kind of modification of Einstein’s relativity principles) is back, and they’ve done a very important cross-check many of us were hoping they would do, which is very good news indeed. Since they say that it confirms their previous result, the plot now thickens considerably; the experiment’s technique is now harder to question, and the long list of possible sources of problems with the experiment is considerably shorter. Obviously this news deserves a long post, explaining exactly what they did and why it is such an improvement. I’ll produce one for you before the weekend is over, possibly as soon as tomorrow. Watch this space!

In the meantime, here’s a guide to past posts, which cover most of what you need to know:

- a catalogue of my several early posts (and a Q&A) on the OPERA experiment, including how you make a neutrino beam and how you detect neutrinos, are here,

- articles that discuss why, if the experiment is correct, certain effects similar to Cerenkov radiation must somehow be shut off, are here, here and here.

- the article that explained that OPERA would be doing this cross-check, and why I thought it was a very good thing, appeared here.

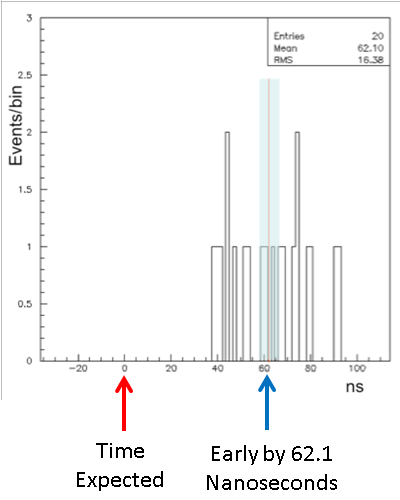

And here’s the key new plot from the OPERA experiment, showing the 20 measured neutrinos arriving 61 ns early, with a spread that is consistent with the uncertainties of the measurement, and not necessarily to be interpreted as the neutrinos having different velocities…

11 Responses

アディダス サンダル メンズ 激売れhttp://www.back2iraq.com/アディダス-サンダル-c-82.html

For me knowing speed of light in a vacuum and speed of light through mediums of expression here on earth, as earth, air and water/ice we are indeed seeing a relationship based on relativistic terms in terms of those mediums yet are still asking about possible deviations in a vacuum. Those expression not held to the domain as mediums.

These distinctions I believe are very important.

Which takes some expressions toward relativistic definitions with regard to Cerenkov, Muon expressions in rock, signatures of dark matter etc. within context of those mediums.

Step off points through which “such signals are not affected by mediums” So why the push? It is indeed a fundamental challenge to what is known in terms of the constant?

Lensing, as an effect in the cosmos?

Best,

Great post, Matt. Did they change anything else with the beam when they did this new test? There was some concern about the knowing the intensity profile of the pions (and hence neutrinos) coming out of the target. Does result address that?

“It isn’t usually like this, folks — this year has been very odd” — you sure about this? This year seems pretty normal to me (except for the absence of anomalies from the LHC). There are a dozen or so weird anomalies a year. We just saw another one a few weeks ago about the variation of the fine structure constant.

Jay [Professor Jay Wacker] — thanks for the note (your comments on today’s article (11/20) would be welcome.) I do not know of any changes to the beam other than the duration of the pulse. What I like about the short pulses is that the intensity profile of the pions, and other subtleties with the pulse shape, become irrelevant, I think. So yes, I think the use of 3 nanosecond pulses to measure a 60 nano-second time-shift removes any such issue. If you disagree, please let me know.

About the anomalies: well, there are always anomalies, that is certainly true — and it is important for the public to understand that. But having the Higgs search *and* the OPERA experiment, both of which are exceptionally public, along with the to-do over the Tevatron W-plus-two-jets “particle” and so forth, has made this a year where the anomalies have gotten exceptional public attention. I haven’t even had time to write about some of the less public ones yet, including the one you mentioned.

So the “spread” is because of uncertainties of measurement, but lag cannot be? Also, “expected time” seems to be based on the known speed of light…so is it not possible that the experiment is providing a more accurate measure of the speed of light? Shouldn’t “expected time” be based on photon detection times in the same setup (assuming optics are advanced enough)? Questions from a lay person with a keen interest in physics.

Good questions:

1) The uncertainties are large enough to explain the variation of the arrival times around 62 nanoseconds but not large enough to explain the shift of the times by 62 nanoseconds. And you can see that in the plot. If you saw that some of the arrival times were, say, 100 nanoseconds late, and others 200 nanoseconds early, with an average of 62 early, you might be suspicious. But that’s not the case.

If OPERA is wrong, it isn’t due to the basic uncertainties but to some larger mistake that shifts everything over by about 60 nanoseconds.

2) No. The neutrinos are (it would seem) arriving with a speed 2 parts per 100,000 faster than light. The speed of light is measured to much higher accuracy than that. And observations of huge explosions in space, which emit light of many different energies, suffices to check, to much, much higher accuracy than a part in 100,000, that light of very different energies travels at the same speed.

3) Ideally, yes, one would actually send a beam of light from CERN to Gran Sasso along the same travel path as the neutrinos, and directly compare. But that’s not possible; the neutrinos travel underground through over 700 kilometers of rock, and there’s no tunnel. Any way you route the light other than a straight line will introduce timing delays and make the comparison as difficult as any other method of measuring the time. It might be possible to design a 1- or 2-kilometer version of OPERA, and then a photon beam could perhaps be sent down the tunnel; but that would require very high precision measurements of the neutrino arrival times, and years of building an experiment, so that won’t happen soon.

Dear Prof. Strassler,

What implications are there to theories such as super string and unified field or other leading theories, if the assumption of a speed limit of the speed of light is no longer valid? Do any of these theories collapse into fewer dimensions or become simplified in any way? Lastly, if c is no longer a limit, does one theory then become a clear front runner?

Sincerely,

Stephen

None of the theories would become simpler, and no theory would become a front runner. All the theories we have use Einstein’s relativity as a base, and until we know what modification of Einstein’s relativity might be necessary, it wouldn’t be clear which theories we have now could accommodate such modifications. We wouldn’t likely know the answers to questions like this for years, or possibly decades.

Perhaps it’s a stupid question, but can it be that the distance has change (shorter) when the neutrinos where shoot out? I think of the movement of the solar-system or galaxies or universe.

We’d see that easily using the GPS system; in fact we’d probably just detect it through cracks in our roads. A shift of 20 meters (60 feet) would be HUGE!